At the National Gallery, a history of photography’s fascination with art

13 November 2012

In the beginning, it was photography that imitated painting. In order to find its own language, the newly born technique couldn’t but look at the century-long tradition of canvas and paintbrush. Yet, when the new discipline finally reached its own maturity, it was the old art that began to draw inspiration from it. Since the post-second world war period, photography has gained more and more space to the detriment of painting, but their relationship has always been one of mutual influence. The exhibition Seduced by Art: Photography Past and Present, set at London’s National Gallery until 30 January 2013, hinges precisely on this concept.

How did early photography regard and “copy” art, both contemporary and ancient? And what lesson do today’s photographers draw from the paintings of the “Great Masters” of the eighteenth and nineteenth century? In order to answer this question, the National Gallery has set the paintings of its own permanent collection side by side with about ninety photographs, borrowed from various European cultural institutions.

The resulting juxtapositions are accurate, but oftentimes also daring. In the section devoted to the origins of the technique, one runs into experimental artists such as Julia Margaret Cameron, Gustave Le Gray and Oscar Gustave Rejlander, who were determined to use every available means (from montage to manipulations), to make their photographic works look identical to the “high” creations of art. Moving on, one reaches the contemporary section. Shots by Richard Billingham, Richard Learoyd and Martin Parr are paired up with paintings by Constable, Ingres and Gainsborough; yet two authors, both born in the Sixties, stand out for their originality and complexity.

The first is photojournalist Luc Delahaye. His “US Bombing on Taliban Positions” lacks the scenic violence effect of other shots taken on the war fields of the Middle and Near East and yet, at the same time, the landscape devoid of any human presence manages to convey the abstract and instant ferocity of military actions in the twenty-first century. For this reason, it legitimately stands the comparison with the “Battle of Jemappes” painted by Vernet in 1821.

The second is Israeli photographer Ori Gersht with his “Blow up”, where the concept of still life is overturned by the artist’s putting tiny explosive charges into the flowers set in a vase. A high-speed camera captures the moment of the blast and freezes it; the scene is flanked by Fantin-Latour’s “The Rosy Wealth of June” (1886).

Seduced by Art is a challenging, contradictory exhibition, which many have criticised on various fronts; sure it will be reminded as an intelligent and well-aimed (hence, admittedly partial) investigation of a crucial relationship for the history of visual art.

Photo credits:

Luc Delahaye, 132nd Ordinary Meeting of the Conference, 2004 – Wilson Centre for Photography – Courtesy Luc Delahaye and Galerie Nathalie Obadia

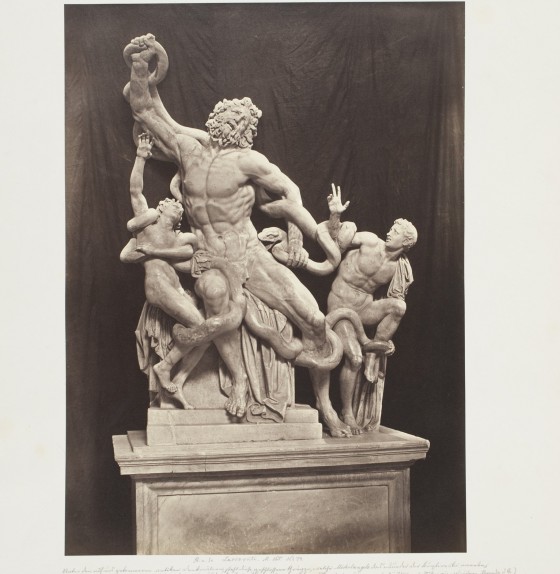

James Anderson, The Laocoön Group, about 1855–65 – Wilson Centre for Photography Wilson Centre for Photography

John Constable, The Cornfield, 1826 – © The National Gallery, London

Richard Billingham, Hedgerow (New Forest), 2003 – Southampton City Art Gallery (11/2004) -© The Artist, courtesy of the Anthony Reynolds Gallery London

Thomas Gainsborough, Mr and Mrs Andrews, about 1750 – © The National Gallery, London

Martin Parr, Signs of the Times, England, 1991 – © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Ignace-Henri-Théodore Fantin-Latour, The Rosy Wealth of June, 1886 – © The National Gallery, London

Ori Gersht, Blow-Up: Untitled 5, 2007 -© Courtesy of the Artist and Mummery + Schnelle, London

Julia Margaret Cameron, Kate Keown, about 1866, Gregg Wilson, Wilson Centre for Photography