One exhibition, one question: the “Century of the child” at MoMA

28 September 2012

It wasn’t just the century of world wars, of great regimes and the ideological clash. The twentieth century was also the century of the child. Almost everywhere in the world, serving the most diverse political and philosophical causes, hundreds of designers built toys, school desks, outfits, books and images for our children. From Bauhaus to America’s Walt Disney, from Italy’s futurism first and Munari afterwards, to 1980s Japanese toy robots.

All together these works form an outstanding cultural property; not only for the exceptional artists and designers who made them, but mostly because they represent an unprecedented collective enterprise—indeed a collective discovery. Only in the last century was childhood acknowledged as a genuine, fully fledged stage of life, as reminded by the exhibition set up until 5 November at MoMA, New York, entitled Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900-2000. As a crucial phase for the determination of one’s personality, childhood not only deserves the most special cares from family and educational institutions, but also specific products from the industry.

The definition “century of the child” goes actually a long way back in time: Swedish social theorist Ellen Key used it in 1900, while foreseeing the beginning of an era in which society would care about child well-being and happiness more and more. What Key couldn’t forecast was the tragic turn history would take when, in the 1930s, the rationalist surge of the first educators (among which Maria Montessori stands out) was replaced by grim indoctrinaton (the Italian table game decorated with a swastika, in fine display along the visit path, is certainly still a disturbing memory for those who saw it).

Apart from the gloomy pre-World War II parenthesis, the visit is absolutely entertaining. One can find what probably is the first toy scooter ever produced on an industrial scale, in Roosvelt’s US. It would cost less than five dollars, though during the Great Depression it still was unattainable for most people. The soviet workers figures created in the 50s by Czech designer Libuše Niklová — the tram driver, the chimney sweeper, the nurse — testify the revolutionary transition from wooden to plastic toys, in the countries joined under the Warsaw Pact; while the vast catalogue of miniature spaceships is a peaceful reflection of the Space Race.

Though the exhibition develops progressively through its seven sections, the difference is striking between the first six decades of the century and the final ones. In the first part architectural projects prevail, of school furnishing and other collective utilities. In the second part toys for private use dominate, while socially engaged projects focus on campaigns aimed at sensitizing the public of child issues in the South of the world. So, here comes the question: if the modernist dream of a world fully respectful of children’s rights has finally come true–at least in the West–what comes after that? Will child design in the twenty-first century give shape to a new “century of the child”? What prospects are there, apart from a century of the child-consumer?

Photo credits:

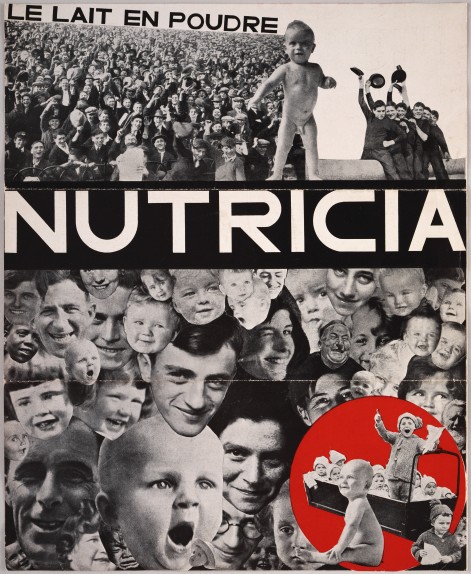

Paul (Geert Paul Hendrikus) Schuitema. Nutricia, le lait en poudre (Nutricia, powdered milk). 1927-28. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Ladislav Sutnar, Build the Town building blocks. 1940–43. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Omnibot 2000, remote-controlled robot. c. 1985. Manufactured by Tomy (formerly Tomiyama), Katsushika, Tokyo. Space Age Museum/Kleeman Family Collection, Litchfield, Connecticut

Gio Ponti. Glass desk. 1930. Manufactured by Vitrex, Sassuolo. Collection of Maurizio Marzadori, Bologna

Elizawieta Ignatowitsch. The Fight for the Polytechnic Schools is the Fight for the Five-Year Plan, and for a Communist Education of the body politic. 1931. Letterpress, lithograph, 20 1/4 x 28 1/4″ (51.4 x 71.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Teaching materials commissioned by Maria Montessori. 1920s. Wood, dimensions vary. Manufactured by Baroni e Marangon, Gonzaga, Italy (est. 1911). Collection of Maurizio Marzadori, Bologna

Holdrakèta and original box. c. 1960. Tin, box: 24 x 6″ (61 x 15.2 cm). Manufactured by Lemezaru Gyar, Budapest (est. 1950). Collection of Joan Wadleigh Curran, Philadelphia

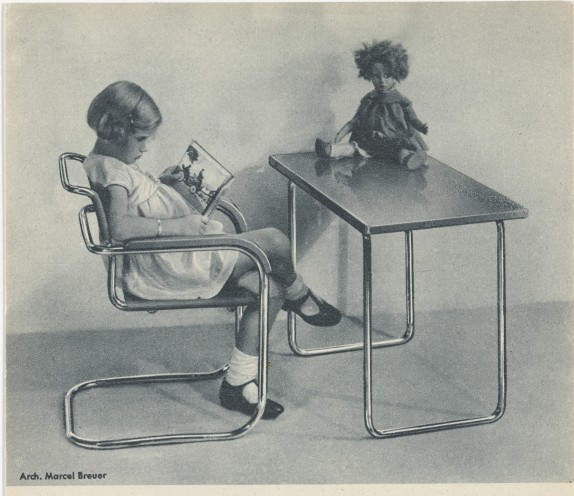

Detail from Stahlromöbel (Tubular steel furniture), loose-leaf sales catalogue for furniture offered by the Thonet Company, showing Marcel Breuer’s B341/2 chair and B53 table. 1930-31. Published by Thonet International Press Service, Koln. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

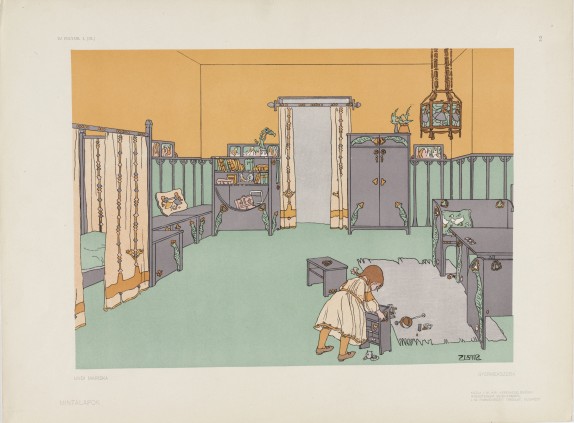

Mariska Undi. Design for children’s room. 1903. The Museum of Modern Art, New York